This record, like many in Rally Week, will take you to another place instead of planned. I’m sure you know perfectly well how the opening ceremony of the WRC season took place this year. And you know, 2021 is the end of the current WRC car era. This story will be about the opening rally of the end of the other World Rally Championship car group – the 1986 Rallye de Monte Carlo.

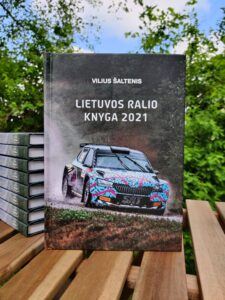

Rallye de Monte Carlo